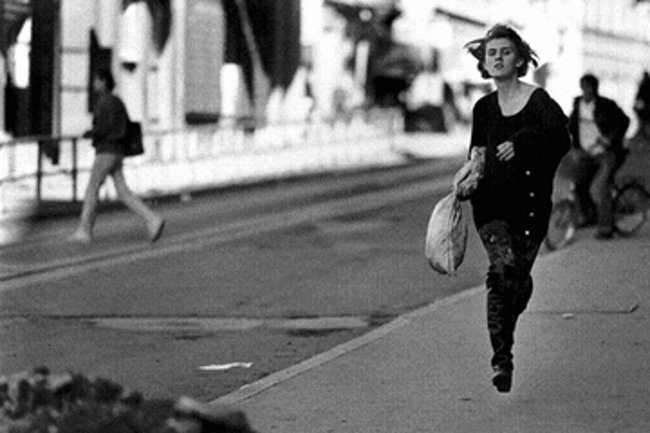

Sarajevo, 30 September 1993. The girl that runs (Photo © Mario Boccia)

The girl that runs. It is the title of a famous photo by Mario Boccia, Italian photojournalist, snapped on September 30th, 1993. A day like any other in Sarajevo, under siege for 17 months, between bombings and snipers. Twenty years later, Mario tells the story

The streets of Sarajevo

Sitting outside a small bar, in a street named after Radojka Lakić (a partisan woman born in 1917 and killed in 1941), Edoardo and I are waiting for coffee. During the war, I have enjoyed here the best Nescafe of my life, prepared with meticulous care, with sugar beaten by hand to mask it as espresso with cream. For us journalists, it costed three German marks. Too many, but well spent.

A working day is almost over. The truce holds. From their positions in the mountains, Serbian soldiers are not firing. The war seems distant though, just a few miles away, the ex-allies Croats and Muslims fight bitterly. East Mostar is besieged by soldiers who pray in Medjugorje. Ethnic cleansing is fierce and mutual everywhere. Not even the most remote villages are spared. Even Počitelj, on the road that runs along the Neretva towards the sea, is razed to the ground. It used to be the village of artists and painters. A white cross, five meters high, was planted in front of the burned mosque. To intimidate, not to pray.

The day before yesterday, the "Bošnjački Sabor", a self-proclaimed, all Muslim parliament, rejected yet another cease-fire proposal by the international diplomacy, based on the partition of the country along ethnic lines. Today, the official Bosnian parliament has ratified that decision.

The arrival of coffee is accompanied by a chilling hiss above us, followed by an explosion that hurts. I take the camera and run to the street where the grenade fell, the street named after Marshal Tito (partisan, Yugoslav president, and founder of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961). Another hiss paralyses my legs. I feel the wall against which I flattened vibrate. The second shot hit the other side of the building. I look from the corner: the road is deserted. I put on the twenty-eight lens and measure the light, flat and without shadows. I get close, but a chipped wall and some rubble mean nothing. There is no picture there. I think of the wounded I saw. Not the dead, but the screams of the light wounded, with splinters and broken bones in the body.

A man shouts to me to stay away. Near the "Vječna vatra" (the eternal flame of Sarajevo that from April 6th, 1946, anniversary of the liberation, commemorates those who fell in the war against the Nazis), on the other side of the road, there is a lobby. A dozen people are there, pressed to one another in silence. "Stay here", he says. Eyes look at me, the tense expressions of dignified people. This is the photo. I hold the camera, the lens is right, but I hesitate. Another explosion. I run outside, I haven't had the strength to shoot. I regret it. Those looks. I felt like an outsider. Privileged and judged for choosing to be there (maybe I'm blushing). At least now I am under fire like the others. I look at what is happening through a lens. The camera is a shield that protects and keeps some distance.

Another, less strong hiss, the explosion is late (a couple of seconds?), further away. I see movement around the marketplace. I go up, mount the two hundred lens, select a fast tempo, control the light. A girl runs towards me. I frame, click, and curse that I have not set the engine on the continuous shooting (not to waste film). Too late, now she is past me, ignoring me. It's over.

Click again. A couple running, a woman across the street, but everything now seems inadequate. I have the look of the girl running in mind. That girl was not running out of fear, but out of anger. Being both under fire does not put us on the same floor. Her anger I can guess, but not share. She is at home, they are firing on her city, her habits, her life. I am a volunteer host (and paid). Part of her anger must be for me, for stealing the intimacy of that race. What am I doing here? "Duty of chronicle", of course, but telling me over and over is not enough. The stomach shrinks again, a closer explosion, and thoughts disappear.

A few minutes pass. Now there is silence. I think maybe I did one good shot. I never stopped walking, looking around. I have not seen any injured, fortunately. I have always felt like a jackal, after those photos.

I try to think. A few days ago, Bosnian Serb Prime Minister Vladimir Lukić, in Pale, had given a reassuring interview. He seemed alien to what was happening in the rest of Bosnia. For him, the war was a residual land dispute between Croats and Muslims, then there would be the official division of the country. Now what? Why have they started to shoot in Sarajevo? Did they want to challenge the decision of the "Bošnjacki Sabor"? Someone will write that these grenades are just a warning. Can people die for a "warning"? What did the girl who ran think? Why not interview her, rather than listening to the usual fanfares? I must not think about it now, I'm here to take pictures and tell the facts.

I go back to the bar. The coffees are still on the table. Edoardo calls me, screaming and swearing at me. To play down the tension, I do a little coup de théâtre: I bring in the cups. I want to say that all is well with a gesture. The bar, like the lobby, is full of people. My hands start shaking, I cannot help it. The coffee, now cold, pops out. Everyone laughs. At least it served for this.

Edo hugs me (I still feel that hold). A girl with an eye patch gives me a brandy. Her name is Amra. She smiles. Later, I learn that her father died a few months before, protecting her with his body when a grenade exploded as they walked out of their house, in Mehmed Pasha Sokolović street (Ottoman Grand Vizier, who built the bridge on the Drina in Višegrad in 1571; his brother was Makarije Sokolović, the Christian Orthodox Patriarch of Peć).

The street signs, in brownish red, tell stories of resistance and inclusion. It could not be otherwise. This is Sarajevo.

This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso and its partners and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The project's page: Tell Europe to Europe.

blog comments powered by